Delta

For upon |River Delta forms as rivers empty their water and sediment into another body of water, such as an ocean, lake, or another river.

River in Egypt

Deltas are wetlands that form as rivers empty their water and sediment into another body of water. The Nile delta, created as it empties into the Mediterranean Sea, has a classic delta formation. The upper delta, influenced by the Nile’s flow, is the most inland portion of the landform. The wide, low-lying lower delta is more influenced by the waves and tides of the Mediterranean.

Lena Delta

A river moves more slowly as it nears its mouth or end. The slowing velocity of the river and the build-up of sediment allow the river to break from its banks and develop new channels, called distributaries. This process is called avulsion. Here, the distributary network of the Lena River delta undergoes avulsion as it empties into the Arctic Ocean in Russia.

Mississippi Delta Formations

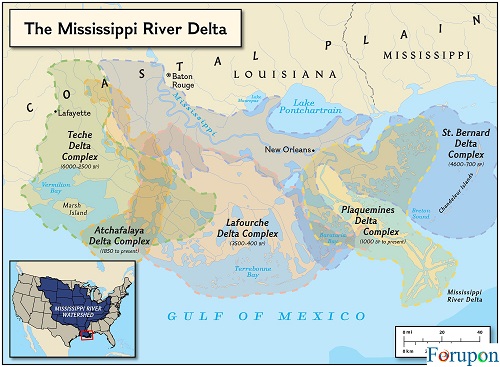

Under the right conditions, a river’s distributary network forms a deltaic lobe. The process of avulsion in deltaic lobes is called delta switching. Over time, delta switching can create entirely new deltaic lobes. Over thousands of years, the Mississippi River formed five major deltaic lobes.

Bengal Tiger

Deltas are incredibly biodiverse wetland ecosystems. The sediments on which they are built are rich in nutrients, fostering a rich plant and microbial community. Even apex predators, such as this Bengal tiger prowling the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta in India, are supported by delta wetlands.

The mouth of the Amazon

Not all rivers have deltas. For a delta to form, the flow of a river must be slow and steady enough for silt to be deposited and built up. Strong waves and tides can also prevent deltas from forming. The Amazon River, above, is the largest river in the world, but strong tides from the Atlantic Ocean sweep sediment away as soon as it is deposited.

Lake Bogoria

One way to classify deltas is by their shape. The classic fan-shaped triangle landform is called an arcuate delta. This beautiful arcuate delta is formed by the Sandai River as it empties into Lake Bogoria in Kenya.

Ebro Delta

A cuspate delta is formed as strong waves shape an accurate delta into a narrower, tooth-shaped formation. The Ebro River forms a cuspate delta as it empties into the Mediterranean Sea near Tarragona, Spain.

Delta Wetlands

A bird-foot delta has few, widely spaced distributaries, making it look like a bird’s foot. The Mississippi River forms a bird-foot delta as it empties into the Gulf of Mexico.

Sacramento Delta

Inverted deltas look like the opposite of a classic arcuate delta. The distributary network of an inverted delta is inland, while a single stream reaches the ocean or other body of water. The delta of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River in northern California is an inverted delta.

Volga Estuary

An estuarine delta is formed as a river that does not empty directly into another body of water but instead forms an estuary. An estuary is a partly enclosed wetland that features a brackish (part-saltwater, part-freshwater) habitat. The estuarine delta of the largest river in Europe, the Volga, forms Europe’s largest estuary as it empties into the Caspian Sea near Astrakhan, Russia.

Ice-Free Delta

Estuarine deltas can have an enormous impact on the habitats and even climate of a region. Here, the flowing water of the Nelson River keeps its delta ice-free, even in the freezing Canadian winter in Hudson Bay.

Okavango Delta

Inland deltas, which empty into a plain, are extremely rare. The Okavango Delta in Botswana is probably the most well-known—and so unusual it is recognized as one of the “Seven Natural Wonders of Africa.”

Delta Distributary

An abandoned delta forms through avulsion, as a river develops a new channel and leaves the other to stagnate. Dry channels in the right of this image mark an abandoned delta of the Chilkat River, as it empties into the Pacific Ocean near Wells, Alaska.

Pearl River Delta

Deltas have been historic sites of trade, and continue to support centers of commerce today. The Pearl River Delta region, in southeast China, supports one of the most urbanized economies in the world, as seen in this image where red indicates vegetation, blue indicates water, pale blue indicates shallow or sediment-laden water, and gray indicates buildings and paved surfaces. The former European colonies of Hong Kong and Macau are welcoming to Western business, and provide an entryway to the massive Chinese market.

Irrigation Canals, Vietnam

Deltas have a rich accumulation of silt, so they are usually fertile agricultural areas. The distributaries of the Mekong River delta near Phung Hiep, Vietnam, have been effectively made into irrigation canals for crops such as rice.

Colorado River

River management involves monitoring and administering a river’s flow (often through the use of dams). River management of the Colorado River nearly prevents it from reaching its delta on the Sea of Cortez, Mexico. The delta (what was once the world’s largest desert estuary) has been reduced to a fraction of its former area. The largest inland body of water (the Salton Sea), to the left in this remarkable image, is not associated with Colorado. Other lakes are created by dams along the river, as a trickle reaches its delta wetlands, visible at the bottom of the image.

Deltas are wetlands that form as rivers empty their water and sediment into another body of water, such as an ocean, lake, or another river. Although very uncommon, deltas can also empty into the land.

A river moves more slowly as it nears its mouth or end. This causes sediment, solid material carried downstream by currents, to fall to the river bottom.

The slowing velocity of the river and the build-up of sediment allow the river to break from its single channel as it nears its mouth. Under the right conditions, a river forms a deltaic lobe. A mature deltaic lobe includes a distributary network—a series of smaller, shallower channels, called distributaries, that branch off from the mainstream of the river.

In a deltaic lobe, heavier, coarser material settles first. Smaller, finer sediment is carried farther downstream. The finest material is deposited beyond the river’s mouth. This material is called alluvium or silt. Silt is rich in nutrients that help microbes and plants—the producers in the food web—grow.

As silt builds up, new land is formed. This is the delta. A delta extends a river’s mouth into the body of water into which it is emptying.

A delta is sometimes divided into two parts: subaqueous and subaerial. The subaqueous part of a delta is underwater. This is the most steeply sloping part of the delta and contains the finest silt. The newest part of the subaqueous delta, furthest from the mouth of the river, is called the Prodelta.

The subaerial part of a delta is above water. The subaerial region most influenced by waves and tides is called the lower delta. The region most influenced by the river’s flow is called the upper delta.

This nutrient-rich wetland of the upper and lower delta can be an extension of the riverbank or a series of narrow islands between the river’s distributary network.

Like most wetlands, deltas are incredibly diverse and ecologically important ecosystems. Deltas absorb runoff from both floods (from rivers) and storms (from lakes or the ocean). Deltas also filter water as it slowly makes its way through the delta’s distributary network. This can reduce the impact of pollution flowing upstream.

Deltas are also important wetland habitats. Plants such as lilies and hibiscus grow in deltas, as well as herbs such as wort, which are used in traditional medicines.

Many, many animals are indigenous to the shallow, shifting waters of a delta. Fish, crustaceans such as oysters, birds, insects, and even apex predators such as tigers and bears can be part of a delta’s ecosystem.

Not all rivers form deltas. For a delta to form, the flow of a river must be slow and steady enough for silt to be deposited and built up. The Ok Tedi, in Papua New Guinea, is one of the fastest-flowing rivers in the world. This river becomes a tributary of the Fly River. (The Fly, on the other hand, does form a rich delta as it empties into the Gulf of Papua, part of the Pacific Ocean.)

A river will also not form a delta if exposed to powerful waves. The Columbia River in Canada and the United States, for instance, deposits enormous amounts of sediment into the Pacific Ocean, but strong waves and currents sweep the material away as soon as it is deposited.

Tides also limit where deltas can form. The Amazon, the largest river in the world, is without a delta. The tides of the Atlantic Ocean are too strong to allow silt to create a delta on the Amazon.

Types of Deltas

There are two major ways of classifying deltas. One considers the influences that create the landform, while the other considers its shape.

Influence

There are four main types of deltas classified by the processes that control the build-up of silt: wave-dominated, tide-dominated, Gilbert deltas, and estuarine deltas.

In a wave-dominated delta, the movement of waves controls a delta’s size and shape. The Nile Delta (shaped by waves from the Mediterranean Sea) and the Senegal Delta (shaped by waves from the Atlantic Ocean) are both wave-dominated deltas.

tide-dominated deltas usually form in areas with a large tidal range or area between high tide and low tide. The massive Ganges-Brahmaputra delta, in India and Bangladesh, is a tide-dominated delta, shaped by the rise and fall of tides in the Bay of Bengal.

Gilbert deltas are formed as rivers deposit large, coarse sediments. Gilbert deltas are usually confined to rivers emptying into freshwater lakes. They are usually steeper than the normal flat plain of a wave-dominated or tide-dominated delta. This type of delta was first identified by the geologist Grove Karl Gilbert, who described mountain streams feeding ancient Lake Bonneville. (Utah’s Great Salt Lake is the only remnant of Lake Bonneville.)

Estuarine deltas form as a river and do not empty directly into the ocean but instead form an estuary. An estuary is a partly enclosed wetland that features a brackish water (part-saltwater, part-freshwater) habitat. The Yellow River forms an estuary, for instance, as it reaches the Bohai Sea off the coast of northern China.

Shape

The term delta comes from the upper-case Greek letter delta (Δ), which is shaped like a triangle. Deltas with this triangular or fan shape are called arcuate (arc-like) deltas. The Nile River forms an arcuate delta as it empties into the Mediterranean Sea.

Stronger waves form a cuspate delta, which is more pointed than the arcuate delta and is tooth-shaped. The Tiber River forms a cuspate delta as it empties into the Tyrrhenian Sea near Rome, Italy.

Not all deltas are triangle-shaped. A bird-foot delta has few, widely spaced distributaries, making it look like a bird’s foot. The Mississippi River forms a bird-foot delta as it empties into the Gulf of Mexico.

Another untraditional-looking delta is the inverted delta. The distributary network of an inverted deltas’ is inland, while a single stream reaches the ocean or other body of water. The deltas’ of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River in northern California is an inverted deltas’. The rivers and creeks of the Sacramento and San Joaquin distributary networks meet in Suisun Bay, before flowing to the Pacific Ocean through a single gap in the Coast Range, the Carquinez Strait.

Inland deltas, which empty into a plain, are extremely rare. The Okavango Deltas’ in Botswana is probably the most well-known—and so unusual it is recognized as one of the “Seven Natural Wonders of Africa.” Water from the Okavango River never reaches another body of water. The deltas spread water and silt across a flat plane in the Kalahari Desert before being evaporated.

An abandoned deltas forms as a river develops a new channel, leaving the other to dry up or stagnate. This process is called avulsion. Avulsion occurs when the slope of a channel decreases and the sediment build-up increases. These forces allow the channel to overflow its banks or levees and find a steeper, more direct route to the ocean or other body of water. The process of avulsion in deltaic lobes is called deltas’ lobe switching. Over time, deltas’ switching can create entirely new deltaic lobes. 1Deltas’ switching has resulted in seven or eight distinct deltaic lobes of the Mississippi River over, at least, the past 5,000 years.

Deltas and People

Deltas are incredibly important to the human geography of a region. They are important places for trade and commerce, for instance.

The booming city of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, sits on the deltas’ of the Fraser River as it empties into the Strait of Georgia, part of the Pacific Ocean. The Fraser Deltas’ helps make Vancouver one of the busiest, most cosmopolitan ports in the world, where goods from the interior of Canada are exported, and goods from around the world are imported.

The Pearl River Deltas’, sometimes called the Deltas’ of Guangdong, is another heavily urbanized river deltas’. 1The Pearl River Delta is one of the fastest-growing centers of China’s economy. The Pearl River deltas’ includes both of China’s two special administrative regions, the former British colony of Hong Kong and the former Portuguese colony of Macau. Hong Kong and Macau are welcoming to Western business, and provide an entryway to the Chinese market. The Pearl River Deltas’ region is growing so quickly, that it frequently experiences labor shortages as immigrants from the Chinese interior settle in the area, seeking a better life and higher wages.

Deltas have a rich accumulation of silt, so they are usually fertile agricultural areas. The world’s largest deltas’ is the Ganges–Brahmaputra delta in India and Bangladesh, which empties into the Bay of Bengal. Bangladesh sits almost entirely on this deltas’. Fish, other seafood, and crops such as rice and tea are the leading agricultural products of the deltas’.

Similarly, the inverted deltas’ of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers in northern California are one of the most agriculturally rich areas in the U.S. The soil supports crops from asparagus to zucchini, wine grapes to rice.

Disappearing Deltas

Extensive river management threatens deltas. River management involves monitoring and administering a river’s flow (often through the use of dams). River management increases the amount of land available for agricultural or industrial development and controls access to water for drinking, industry, and irrigation.

Engineers and government officials must consistently debate the interests of agriculture, industry, the environment, and citizen safety and health when putting deltas’ wetlands at risk.

River management in Egypt has radically altered the way land is farmed around the Nile Deltas’, for instance. Construction of the Aswan Dam in the 1960s reduced annual flooding of the deltas’. This flooding had distributed silt and nutrients along the banks of the Nile. Today, Egypt is much more reliant on fertilizers and irrigation. The Nile Deltas’ is also shrinking as a result of the Aswan Dam and other river management techniques. Without silt and other sediments to fortify the deltas’, the waves of the Mediterranean Sea are eroding the deltas’ faster than the Nile can replace them.

In the United States, dams on the Colorado River nearly prevent it from reaching its deltas’ on the Sea of Cortez, Mexico. The ecosystem (what was once the world’s largest desert estuary) has been reduced to a fraction of its former area, and many indigenous species are vulnerable, threatened, or endangered.

Finally, decades of river management prevent the Mississippi River from naturally flowing through its deltas’ wetlands. Like the Nile Deltas’, the Mississippi Deltas’ is also eroding. According to Drawing Louisiana’s New Map, 62 square kilometers (24 square miles) of wetland was lost each year between 1990 and 2000—that’s about one football field of mud washed into the Gulf of Mexico every 38 minutes. This situation contributed to the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

The triangle-shaped Nile Deltas’ is a perfect example of arcuate deltas’.

Photograph courtesy Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC

Deltas’ Blues

Deltas’ blues is a style of music developed by African-American artists living and performing in the Mississippi Deltas’ region of the southern United States. The Mississippi Deltas’ is actually a flood plain between two rivers in northwestern Mississippi, the Mississippi and the Yazoo, It is sometimes to as the Yazoo-Mississippi Deltas’.

Slide guitar is one of the standard instruments used by Deltas’ blues musicians, while familiar topics include poverty and injustice. Robert Johnson, widely recognized as one of the greatest guitarists of all time, played the Deltas’ blues. Listen to Robert Johnson here.

The article was originally published here.

Comments are closed.